Every British person needs to visit Belfast. Despite being one of the last cities I visited in 2015, Belfast was arguably the most interesting. The city is one of the most unique in Europe today (let alone the British Isles), thanks to its brutal history, divided communities and the seemingly fragile peace between them.

After two days in the city, I came to the conclusion that every British person should visit Belfast. And here’s why.

Queens University, Belfast

West Belfast: The Troubles

Growing up in the UK, the term ‘the Troubles’ was used often, and I had at least a general awareness that Belfast was not a particularly safe place to be. Likewise, I knew that Northern Ireland was in conflict but I had little to no understanding of why that was and what role the UK played in it. And that’s as much as I knew for a very long time.

So what were the Troubles? Naturally, the history of Northern Ireland is incredibly complex and so I won’t attempt to try and give a detailed explanation, but in simple terms, the Troubles was a very violent period of conflict between the Republican communities (who wanted to reunite with the Republic of Ireland) and Unionist communities (who wanted to remain in the United Kingdom) in Northern Ireland. These groups which were generally split along religious lines (Catholics being Republicans and Protestant being Unionists or ‘Loyalists’).

What started the Troubles? In oversimplified terms, the unrest started in the late 1960s as a reaction against prejudice towards the Catholic community in Northern Ireland. Catholics had formed the majority in Ireland before the Partition in 1922 and had endured unfair treatment as a minority in Northern Ireland.

The Troubles officially came to an end in 1998 with the Good Friday agreement, but unrest has flared up sporadically since then.

Read more: A road trip from Belfast to Dublin

A guide to West Belfast

Events tied to the Troubles took place across Northern Ireland, Ireland and Great Britain, but West Belfast can be considered a ‘heartland’ of the conflict, being home to pockets of both staunch Unionists (centred along Shankill Road) and Republicans (concentrated near Falls Road).

Neighbourhoods in this area of the city are clearly marked with Union Jacks and Ulster flags or Irish flags. The famous Black Taxi Tours of the city concentrate on this area to explain the Troubles. But luckily, I had my very own personal tour guide who grew up around the Falls Road.

So what are the main sights of West Belfast?

Things to see in West Belfast

The Peace Walls

It was in West Belfast, in an attempt to bring stability to the area, that the city’s Peace Walls were erected as a temporary measure in 1969, intended to last only six months – the majority of which are still standing today.

The Peace Walls (or Peace Lines) are the most striking feature of West Belfast and many have actually grown higher since the Good Friday Agreement. There are several passages through the walls, but many of these are shut during evenings and weekends in order to quell tensions.

It is genuinely such a bizarre feeling to walk around these walls and see a division many would sooner equate to 1980s Berlin than present-day Belfast.

The walls feature a large collection of murals. It’s also common practice for tourists to sign the walls. Cupar Road in the protestant area seemed to be a popular spot on our visit.

Touring the Murals of West Belfast

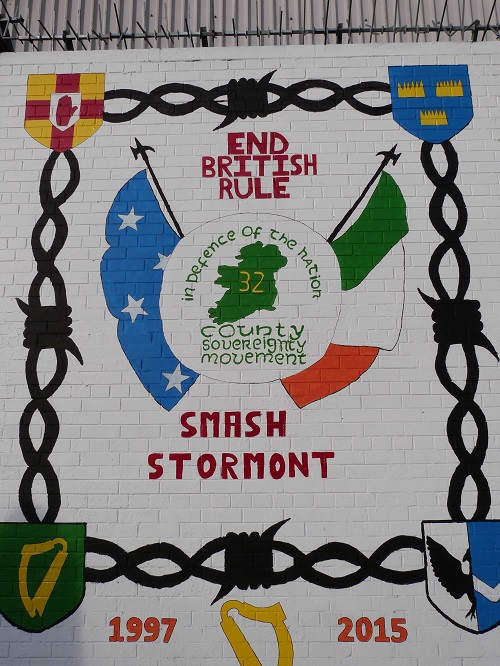

Countless murals can be found in West Belfast, particularly along Falls Road at the start of the Peace Walls. Here you’ll find paintings dedication to peace and solidarity to other causes, such as Nelson Mandela’s imprisonment and the plight of Palestine, which both strike a chord with Republicans.

While the government gives grants to community groups who wish to create a peaceful mural, several images depicting war or fallen soldiers can be found.

Probably the most famous of Belfast’s murals is dedication to Bobby Sands, leader of the 1981 Hunger Strike.

Memorial gardens of West Belfast

Memorial gardens to those who lost their lives during the Troubles are found throughout West Belfast and are well-maintained, though many are kept locked.

Police stations

One interesting feature of Belfast is its highly-fortified police stations, which look more like garrisons. Personnel from the army were based here making them an obvious target with a need for high security.

Belfast today: a delicate balance

Despite the official end of the Troubles with the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, tensions and unrest do still flare up. Major protests occurred in 2012, for example, when the government voted to only fly the UK flag on certain days of the year.

In fact, since 1998, many of the Peace Walls have actually grown higher. The government has stated that it is committed to bringing down the Peace Walls by 2023, but my personal tour guide was sceptical.

For many, the walls bring security

She explained that the walls aren’t simply a sign of division but a symbol of security for people. If walls were suddenly torn down, those who have grown up with them or close to them would be left feeling exposed. Similarly, the fortified police stations and armoured police cars add to a feeling of security for some people.

Being there, it seemed quite easy to believe – the walls and the division are so striking in the city, it’s hard to imagine them not being there. It’s not hard to imagine that the destruction of such an imposing structure would have a psychological effect, too.

Northern Irish identity

Titanic Belfast is a symbol of both Belfast’s history and its future

But what will the future mean for Belfast? With such a clear division between those identifying as Irish and those as British, can a common identity be forged?

According to my guide: yes. Belfast – and Northern Ireland as a whole – is on the up: Titanic Belfast and Game of Thrones have brought record amounts of tourists to the area and the economy is recovering. Plenty of young people are beginning to take pride in their Northern Irish identity – something that will most likely continue if more ‘outsiders’ with no historic ties move into the area.

Of course, the Scottish referendum brought some debate about a similar scenario in Northern Ireland on its Irish or British future, but as a friend put it:

“If we had a referendum for Northern Ireland, I think we’d just find out that nobody wants us.”

Belfast as a British tourist

Belfast Town Hall | Credit: Nicolas Raymond

At the start of this post, I said that all British people should go to Belfast. I think visiting the city as a Brit is a unique experience – on the surface, Belfast looks like any other in the UK. The road signs are the same, the architecture is familiar and you’ll find all the same shops you’re used to.

But enter into a protestant, unionist neighbourhood and everything feels totally different: the Union Jack is everywhere. Curbs on the road are painted blue, white and red. Imagines of poppies and fallen WWI soldiers are depicted in huge murals. These neighbourhoods are British – but not as I’m used to it.

The patriotism has an aggression to it that is unfamiliar. To be honest, I felt uncomfortable. It was a strange feeling. But of course, the history of the place is alien to me – this is the complicated reality in Belfast.

I think that it’s important for anyone to go and learn more about the history of Northern Ireland. I really believe the history of Anglo-Hiberno relations should be taught in schools in order to understand the complexity of our close relationship with Ireland. What’s more, I think very few people appreciate that Belfast is still a divided, walled city in our own back garden.

Anyone who does visit Belfast will be rewarded, not just with a keener insight to recent history, but with a fun, lively city that I absolutely loved.

I’ve briefly been to Belfast (an unintentional 4-hour layover resulting from missing a plane from America to Scotland, and being re-routed via N. Ireland). I wasn’t there long enough to have the same experience as you, but I did find it pretty interesting, as I took a class on Irish literature while in the UK, and seeing all the signs of the Troubles that had featured so prominently in the works I read was pretty neat! I had similar feelings on a previous trip to Dublin. Excited to do a summer holiday in Ireland this year (Republic & Northern, if all goes well!), esp since it is the 100 year anniversary of the Easter Rising!

This year would definitely be the perfect time – there was a lot going on in Dublin in preparation for the anniversary when I was there and 1916 is just printed everywhere! An exciting time to go I’d say.

I love Belfast (and Dublin ) and can highly recommend the black taxi tours. A fascinating history, lovely friendly people and as well as the vibrant and cosmopolitan city, 20 minutes out, is the fishing village of Portaferry situated on the very scenic Strangford Lough, and the Antrim coastline is stunning (also home to the Giants Causeway)

Couldn’t agree more Angie! Thanks for your comment 🙂

I loved Belfast, and would love to get to Derry next. History and politics normally bore me rigid, but when you can take the black cab tour and see the murals for yourself, it’s so interesting.

I’m normally a bit history buff but I know what you mean – Belfast feels a bit like living history because the affects can still be so clearly seen. I’d be curious about Derry too so let me know what it’s like if you get there first!

I’ve been living in Belfast for nearly 3 years now (I’m Belgian) and I think you captured the fragile peace very well. It’s an interesting story, with an interesting history and I’m really curious to see what Belfast will be like in 10-20 years from now, when wounds are starting to heal. The majority of the people can see beyond the division and I would love to see the “walls” coming down, but I also know that indeed for a lot of people living there, they see it as a major protection. Time will tell…

Definitely – it must be interesting living in Belfast as a foreigner and someone ‘neutral.’ But what an exciting city to live in!